As the year comes to a close and my inbox fills with last minute e-solicitations, I’ve found myself reflecting on things I’ve learned over my 25+ years in the cultural sector, especially relating to fundraising and philanthropy. This sent me to my archives, where I found a post from 2012 that I thought was worth re-sharing. I hope you find some valuable nuggets here about The Art of Fundraising. I wish you all the best for a successful year-end that sets the stage for an inspired 2016. —AB

I’ve spent a good portion of the past two-plus decades engaged in building resources for the arts, especially through fundraising. I’d like to think that I’ve learned a few things, and shared what I’ve learned with others. Along the way, I’ve developed some maxims that reflect my experiences and philosophy about this work. Things like:

a. There is an art and a science to fundraising – you can learn the theories and techniques, but applying them creatively is where the magic happens.

b. Fundraising doesn’t occur in a vacuum. It’s a team effort that embraces the full organization and involves everyone, from the intern to the trustee to the volunteer.

c. There’s nothing more important than doing your homework. Success comes from combining your passion and dedication with substantive preparation.

d. Great fundraisers are great storytellers.

e. At its core, fundraising is community building. It’s about inspiring engagement that leads to investment.

f. The sweet spot of cultural fundraising is the intersection of program (what you offer), brand (who you are) and audience (who you serve).

g. You must be personally committed to this work and the organization you represent because you can’t feign authenticity.

h. Fundraising is a lot like life: challenging, uplifting, unyielding, transformative. It is what you make it.

"At its core, Fundraising is community building."

Then I re-read Ken Burnett’s Relationship Fundraising and was reminded that wise souls have been sharing their experiences long before I even knew that there was such a profession as fundraising, let alone that I would explore it in the cultural sector.

In his book, Burnett summarizes the lessons he learned under the wing of Harold Sumption, considered the father of 20th-century fundraising in the U.K. Below are Burnett’s Essential Foundations of Fundraising^. (Disclaimer: I've taken some minor license here, converting a bit of Burnett's prose to American English grammar and currency, eliminating a few for redundancy, plus added some commentary of my own, in italics). Here goes:

- People give to people. Not to organizations, mission statements or strategies. You’ve heard it before: it’s all about relationships.

- Fundraising is not about money. It’s about the necessary work that needs doing. Money is the means to an end.

- Fundraisers need to be able to see things through their donors’ eyes. If they are to understand you, you are first to understand them.

- It helps if you are a donor yourself. No one should be a fundraiser without first being a donor. If you ask, you gotta give, too.

- Friend making comes before fundraising. Fundraising is not selling. Fundraisers and donors are on the same side. To be clear, your job as a fundraiser is to make “friends of the institution.”

- Fundraising is about needs, as well as achievements. People will applaud achievement, but will give to meet a need. Need is a subjective term when it comes to cultural fundraising; purpose or impact often carry more weight than need.

- Fundraisers need to learn to harness the simple power of emotion. Fundraising has to appeal first to the emotions. Logic can then reinforce the appeal. People respond to meaning, and they remember stories over facts. See AB maxims d and g.

- Offer a clear, direct proposition to which people can relate. For example, “Make a blind man see. $15.83.” Expose a child to the arts. Priceless.

- First open their hearts and minds. Then you can open their wallets. But if you think of your donors as walking PayPal accounts, go sell shoes.

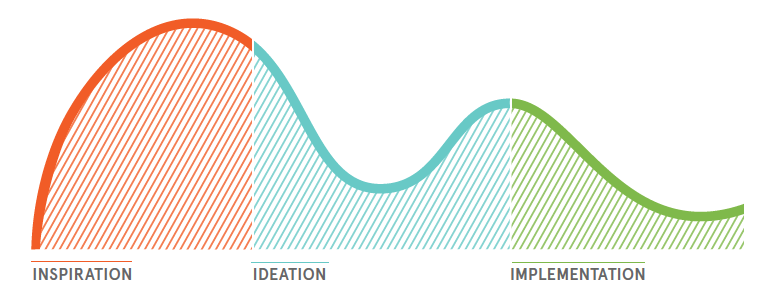

- Don’t just ask people to give. Inspire them to give. Fundraising is the inspiration business. You must find your own inspiration first before you can effectively engage others.

- Share with your donors your problems, as well as your successes. Honesty and openness are usually prized more highly than expert opinion and apparent infallibility. Honesty + transparency = trustworthiness.

- You don’t get if you don’t ask. Know whom to ask, how much to ask for and when.

- Present your organization’s “brand” image clearly and consistently. Your organization will benefit if your donors can readily distinguish your cause from all the others. Good branding – how your patrons see and experience you – communicates who you are and reinforces your values.

- Successful fundraising involves storytelling. Fundraisers have great stories to tell and need to tell them with pace and passion to inspire action. See AB maxim d.

- Great fundraising is sharing. Share your goals and encourage full involvement. When donors truly become involved in your campaign, great things happen. See AB maxim e.

- The trustworthiness of fundraisers and their organizations are the reasons both to start and to continue support. Trust appears to increase in importance as people get older. See #11.

- Great fundraising requires imagination. Too much fundraising looks like everything else. See AB maxim a.

- Great fundraising is getting great results. If your results are mediocre, your fundraising probably is, too. This work is karmic – what you put out in the world really does return to you, sometimes in the most unexpected ways.

- Always be honest, open and truthful with your donors. Donors will not forgive you if you are less than straight with them. Transparency isn’t a buzzword – it is your word.

- Avoid waste. Donors hate waste. And don’t look too slick, either. Most donors don’t want to pay for slick. Polished, yes. Slick, no.

- Technique must never be allowed to obscure sincerity. As all actors know, you can’t fake sincerity. See AB maxim g.

- Great fundraising means being “15 minutes ahead.” To keep just a little bit ahead, you have to learn to spot opportunities and take (careful) risks.

- Fundraisers should learn the lessons of history and experience. Anyone who wants to be an effective fundraiser needs first to do some homework. See AB maxim c.

- Always say “thank you,” properly and often. It’s also a good idea to be brilliant at welcoming new donors when they first contact your organization. Stewardship is not about getting the renewal – it's a way of being.

- Be modest and unassuming. Because it takes a coordinated effort and many people to bring in a gift. See AB maxim b.

As Burnett relates in the introduction to the second edition of his book, "Fundraising is more than a job...It is a powerful force for change...and should be an inspirational beacon of hope."* These principles have withstood the test of time, and I'm sure you have a few of your own to add. What are your favorite tenets of fundraising?

Citations

^ Burnett, Ken. Relationship Fundraising. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2002, p. 28-29.

* Ibid, p. xxvii.